How Russia got "into" the United Nations: Vorontsov, USSR→RF Representative AND Security Council President at the time - Knowledge is Power

How a traitor USSR ambassador and GHW Bush abused the Presidency of the UN Security Council to deceive the world. Audio and English transcript of his 2002 interview, hidden in the UN Russian archives.

How a traitor USSR ambassador and the GHW Bush administration abused the Presidency of the UN Security Council to deceive the world. Audio and English transcript of his 2002 interview, hidden in the UN Russian archives since 2015.

Background

On 24 December 1991 Yuli Vorontsov, USSR’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, formerly First Deputy of Foreign Affairs of the USSR, “transmitted” a letter from Boris Yeltsin “informing” the UN Secretary-General that the “Russian Federation” (which was not its name at the time) was “continuing” the USSR’s memberships of the United Nations and Security Council veto, and requesting Vorontsov be accredited as Permanent Representative for the Russian Federation.

Boris Yeltsin was President of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), a country which had never been a member of the UN so had no standing to communicate with the Secretary-General1.

What is more, by that time the RSFSR was a completely separate, independent country from the USSR, having formally seceded from the USSR, declaring that the USSR ceased to exist, on 8 December (ratified by the Russian government, notified to the UN and circulated by the UN to its Membership on 12 December 1991). The USSR had not “ceased to exist”, but continued (with the 8 remaining members), actively exercising its UN memberships2. What was Vorontsov, the representative appointed by the USSR, doing “transmitting” a letter “informing” that another country was “continuing” the UN memberships of the State he was supposed to be representing? Exercising the USSR’s membership to do so?

There is no evidence that Vorontsov had any instructions or authority from the USSR to do so. No agreement is indicated by either the President of the USSR Mikhail Gorbachev who had not resigned, or the Supreme Soviet of the USSR which had not acknowledged the Accords and Protocols stating it had ceased to exist3 ?

It was also notable that, while Belarus delivered a letter to the Secretary-General the same day (24 December 1991) advising it had renounced the USSR, which was fully circulated to all UN members (even though it made no change to any UN memberships), notification of the Alma Ata protocols signed 3 days earlier (by which the 8 remaining USSR member states abolished it) was withheld until 30 December. (Then it. too, was circulated to all UN Members, unlike Yeltsin’s letter - which was never “issued as a UN document”.)

As President (as representative of the USSR) of the United Nations Security Council for December 1991, it appears Vorontsov ensured that “the whole process looked outwardly like a simple sign change at the table of delegations to the General Assembly and the Security Council.“ That Yeltsin’s letter never went before the General Assembly, was never circulated to the UN members, was concealed from the world by the UN Secretariat [until 2022], and that the membership issue was never considered or voted on.

Here is the interview where Vorontsov (who died in 2007) says as much, and describes what really happened.4

(Spot the invisible elephant in the room: The UN Secretary-General Javier Felipe Ricardo Pérez de Cuéllar de la Guerra (AKA Javier Pérez de Cuéllar), responsible for circulation of UN correspondence, and compliance of the UN administration with the law, upon whom the membership rely for guidance on the law - who hid Yeltsin’s letter from the UN members and, according to a New York Times report, apparently accepted “credentials” for a state which was not a member of the UN. In violation of the UN Charter and Rules.)

Significant quotes:

other countries in the UN started objecting willy-nilly

It is not a permanent member of the Security Council, as it is not listed in the UN [Charter]

I had to talk to the secretary general here, too, and with the legal department

the chairman of the General Assembly at the time requested the opinion of the international court

[01:23] the International Court of Justice responded, by the way, in my presence in a phone call7,

And said "whatever you decide at the UN, that's how it's going to be"8

[01:58] we've had some good co-operation with Western leading countries and primarily with the United States.

American lawyers gave us a very a good legal option that argues that what belongs to the Russian Federation and what does not, has no precedent.

They suggested that, in our application for the, to change the name, as we said at the time, of the country, we pointed out that the Russian Federation is the successor of the Soviet Union.

And it's that word "continuator" that has helped a lot.

A continuator means a seat on the Security Council continues to be Russia's.

Continuer.

… after all this talking, negotiating and excitement, it was all taken normally.

And in fact the whole process looked outwardly like a simple sign change at the table of delegations to the General Assembly and the Security Council.

And there appeared a place Soviet Union, Russian Federation, sign.

But before that, there was a lot of controversy and strife.

[05:42] the wording that was used, yes, it was recommended to us by Western countries, including the United States.

[07:48] Confrontation is a thing of the past. Unnecessary confrontation, when we were like bulls pointing our horns at each other and not doing the right thing, and it's time to co-operate.

(Spot the invisible elephant in the room: The UN Secretary-General Javier Felipe Ricardo Pérez de Cuéllar de la Guerra (AKA Javier Pérez de Cuéllar), responsible for circulation of UN correspondence, and compliance of the UN administration with the law, upon whom the membership rely for guidance on the law - who hid Yeltsin’s letter from the UN members and, according to a New York Times report, apparently accepted “credentials” for a state which was not a member of the UN. Without any authority to do so))

The video

From the horse’s mouth: how the fraud was done in the UN, and by whom.

(Trump’s lawyers would be proud of this!)

Video in web page article dated 19 October 2015: From the UN Radio archive: Ambassador Yuli Vorontsov on how Russia became the “continuator of the USSR”, 2002, interviewer Yevgeny Menkes (Menkes was working for Tass around 1990, Vorontsov died in 2013.)

(It’s only in Russian, no English page.) Best web page translator addon - TWP!

https://web.archive.org/web/20200827092957/https://news.un.org/ru/audio/2015/10/1030441

I have added English subtitles by AI. You can do this yourself, using happyscribe or another captioning service.

The transcript

(of English subtitles, AI generated by Happyscribe, emphasis and sub-headings added):

[00:00] [I] Yuli Mikhailovich, how do you remember those days at the end of December 1991,

when Russia notified the UN that it was inheriting the Soviet Union membership in the UN and the Security Council?

[00:12] [V] Well, those were tough days, because the process of transition from the Soviet Union to the Russian Federation was involuntary.

We didn't want it, but

other countries in the UN started objecting willy-nilly.

There were many proposals that the Russian Federation joined the UN as a new member, a much lesser Russian Federation, so as not to take the [Soviet Union's] place.

It is not a permanent member of the Security Council, as it is not listed in the UN [Charter].

The Charter specifies the Soviet Union.

And such conversations went on, and immediately there were legal disputes and questions of what to do?

And so for, I'll tell you, for many days.

[00:57] I had to talk to the secretary general here, too, and with the legal department,

and to the point where

the chairman of the General Assembly5 at the time requested the opinion of the international court

[There is NO RECORD of this in the UN public records - KIP]

Europe was on the phone.

How is this case to be handled?

Can the General Assembly automatically transfer6 the place of the Soviet Union to Russia?

[01:23] Thank God, the International Court of Justice responded, by the way, in my presence in a phone call7,

And said "whatever you decide at the UN, that's how it's going to be"8

So that's why we closed that side.

[01:37] But there was talk that replacing the Soviet Union in the Security Council should go to some other country,

and some hinted directly that Japan or Germany, or better yet a permanent member, let it be

And Russia would not be a permanent member.

And here we had to work, of course, with everyone.

[01:58] And we've had some good co-operation with Western leading countries and primarily with the United States.

American lawyers gave us a very a good legal option that argues that what belongs to the Russian Federation and what does not, has no precedent.9 They suggested that, in our application for the, to change the name, as we said at the time, of the country, we pointed out that the Russian Federation is the successor of the Soviet Union. And it's that word "continuator" that has helped a lot.

A continuator means a seat on the Security Council continues to be Russia's.

Continuer.

The remaining countries, former republics of the Soviet Union were new, independent states.10

They could not be the continuators.

We're the continuator.

That's how this issue was resolved.11

But it was a lot of excitement, a lot of negotiation, talking of everything.

All in all, those were challenging days.

[03:07] [I] So what was the formula that ended up being put into practice?

You received the message from President Yeltsin that you gave to the UN leadership?

[V] Yes, to the Secretary-General,

which said that we, the Russian Federation, as the Soviet Union's successor at the United Nations,

notifies you that the name of the country will now be different from [changed to] the Russian Federation.

All this after all this talking, negotiating and excitement, it was all taken normally12.

And in fact the whole process looked outwardly like a simple sign change at the table of delegations to the General Assembly and the Security Council.

And there appeared a place Soviet Union, Russian Federation, sign.

But before that, there was a lot of controversy and strife.

[04:02] [I] I have to assume those were exciting days for you, in particular, personally?

[V] Well, of course.

The very fact of the collapse of the Soviet Union, all of this was at the time very much experienced by all of us very much.

And then there's the possible loss of a UN seat.

Get in the general queue, you should be welcomed as a new member.

It was all very unpleasant, of course.

Unfair, for one thing, and unpleasant, for another.

So we were worried a lot.

[04:30] [I] What about the flag?

Did you get a new flag too?

[V] The flag was immediately handed a new one.

And there was no problem here.13

We had it ready in advance, of course, and everyone picked it up.

Then, too, with the shift when the change plaque on the desks of both the General Assembly and the Security Council.

[I] What became of the old Soviet one?

[V] They put it on some distant shelf on the representative's store room and left it there.

[04:56] [I] Understandably, there was a lot of speculation in those days as to whether or not - Whose scenario these events unfolded in.

[Q] In particular, there were rumours that the very idea of a message from President Yeltsin to the Secretary General was allegedly invented by the permanent representative and the U.S., U.K. and France.

What was it really like?

[V] This is such an un-spoiled phone.

About what I told you, that they recommended that we use the formula. On continuity. Yes, it was.

And the message really needed to be sent.

It's an official act, so to speak.

And no one could tell us that scenario, because it had to be done, it was clear to everyone, including us.

The message is self-evident.

[05:42] But the wording that was used, yes, it was recommended to us by Western countries, including the United States.

They have very good lawyers, They certainly have found good form.

[05:54] [I] It's been 10 years today since those days, since that period of time.

What do you see as the significance of this transformation? Still, these are indeed extremely rare events.

[V] For the UN is very rare, I would say unique.

in relation to the great power that our country is.

That is, of course, if it were any other way, it would be a shock to a lot of people and actually change things in the world.

No, it was an important event, absolutely.

But it was all outward, so to speak.

[06:35] Internally, it was important that there was a change in our foreign policy line from the Soviet Union to the Russian Federation.

And that was the most important thing.

And it wasn't easy, because, of course, all superfluous, ideological things disappeared from Russian politics.

And the national interest and the interest

of protecting the world, the interest, the reduction of the race, the cessation of the arms race this was maintained.

So we took something from the old, we gave up something from the old.

It was a complicated process.

[07:09] [I] What have these events highlighted about the UN as an organisation?

[V] Well, the organisation was certainly undergoing some changes by this time.

But at the UN, the end of the Cold War and the emergence of the Russian Federation in the place of the, of the ideology of the Soviet Union was certainly a great, I would say, a fresh wind.

A fresh breeze blew through all the halls.

Our position has become not delegated, but something more universal.

And it was important for making decisions and resolutions and stuff like that.

Particularly important in the Security Council.

[07:48] Confrontation is a thing of the past. Unnecessary confrontation, when we were like bulls pointing our horns at each other and not doing the right thing, and it's time to co-operate.

Now that co-operation is starting to show primarily in the Security Council, and any vetoes have been put on the back burner.

And that's it.

It wasn't the veto that mattered anymore, it was agreement, agreement on decisions of one kind or another.

Of course it came to work better, I'll tell you, more in line with the Charter of the United Nations than before.

[I] Do you consider yourself fortunate to be a participant in, direct a participant in these events, given that you've been at the U.N. for almost half a century. you've been involved with the UN since the early '50s? Do you consider this to be the peak of, say, your diplomatic career?

[V] No, I wouldn't say that.

Because there were further events that, were generally of a substance more important than this event.

But I didn't say it was a happy accident either, because there was nothing happy about it.

There was a lot of excitement, there was a lot of foreplay.

And then, of course, the disappearance of the Soviet Union was also a complicated matter.

After that, conversations began to emerge, that Russia is no longer a great power and so on.

It was also unpleasant.

So the happy ones are few and far between here.

But the fact is, it's been a lot of work to work seriously and healthily, and the result was good.

We have maintained all our positions as a great power in the Organisation of Nations.

It certainly leaves satisfaction.

[09:26] [I] For many decades, there was a representation of the Soviet Union at the UN. A large Union mission and two smaller missions, a Ukrainian mission and a Belorussian mission.

Suddenly there are 15 standalone missions.

What are your lasting impressions of this divorce?

[V] Well, on the one hand,

it was kind of a shame that we're suddenly developing on some individual parts, into some kind of blobs, I'd say.

All in all, it was one, there's a whole community of little droplets.

But, on the other hand, these countries, the new countries, the former republics of the Soviet Union

were very enthusiastic about becoming members of the Organisation, the United Nations, on an equal footing with many other countries.

They had a big upswing.

Ukraine and Belarus, they've kept their fortunes, so to speak, independent states, but they were members of the UN before that.

But many others were very happy to be recognised by the world.

Well, in a way, we were happy for them.

Of course, they were kind of relegated back then, during the Soviet Union, from international affairs.

Now they're getting into international affairs.

On the other hand, it was a bit, I'd say, unusual.

Not that it's offensive, but it's kind of unusual.

Suddenly we have split up and now make up a large number of different countries.

But the main thing was not to lose contact with each other.

We then did this in practical work as well.

And that's it.

Well, don't forget each other in the big one in the family of organising nations when everyone's gone their separate ways.

And we did have a lot of common ground.

[11:15] [I] And do you remember this moment when they accepted a large group of states at the same time [into the UN]?

[V] It was. It was an interesting moment.

It was at the same time at the same meeting

The General Assembly leaders stood up

the newly independent States to the podium of the vote and their reception.

And here, of course, I think I did the right thing when I went first.

Then, after the voting took place, I would be the first to approach each one

the delegation, who were already sitting there under their plaque and congratulating them on joining the United Nations.

Some of the delegation looked at me in surprise for some reason.

What's to be surprised about?

Indeed, have become members of the Organisation of Nations.

We weren't like strangers before.

It was my duty to congratulate them.

But the fact that I was the first to congratulate, produced.

Then I was told my impression on the rest of the General Assembly.

Everyone watched Russia in amazement, It doesn't take offence, on the contrary, it comes over and congratulates me.14

The first one was, to my mind, correct.

[I] Yuri Mikhailovich, was it difficult at that time to period of time to represent our country in the international arena?

After all, the new structure of management and contacts with the centre [Kremlin], apparently, was not established immediately.

[12:34] No, not right away. And confusion.

There were many in the centre [Kremlin],

what constitutes the foreign policy of the new Russian Federation, democratic state, unlike the communist Soviet Union.

And attempts have been made to splash out with water and child, and give up everything just because it was under the Soviet Union.

There was a lot of confusion, and giving up something completely unreasonable because it wasn't

ideological policy, much of the Soviet Union, and national interests. The country is big, they can't be splashed with any ideological water.

national interest or national interest.

[13:19] That's why the instructions from the centre [Kremlin] came

[13:23] often violent and incomprehensible, which sometimes had to be challenge,

veto instructions on unnecessary issues.

I had to grab the telephone receiver and with Minister Kozyrev then was “Why do you need to use the veto?”

And “gone are the days, what's the point?”

Didn't talk me out of it.

It's much needed.

This is to show that Russia still has veto power.

I'm saying you don't have to show anyone anything for that.

Everyone already knows that.

Yes, we have veto power.

Why do we have nuclear weapons?

It's not like we're throwing it into different

territories every day to show it off everyone knows we have it, but the supervisors will review it.

You know how to argue? The minister says No, do it.

And I had to.

I had to do it.

And stupidly so.

I threw my hands up in the Security Council and vetoed it.

Everyone looked at me with great surprise. What are you doing?

And I spread my hands, I said, "Well, what can I do?

The instruction is to veto on a matter of very little importance, and a matter that was completely irrelevant.

Kozyrev told me that's a good thing it's not significant.

We're not going to use the veto on the big stuff.

And this is where we have to demonstrate that we have it.

[14:41] And three days later, the issue was put back on the table.

I prompted all my colleagues on the council You put it up again, we'll vote humanly.

Put it up again.

I told Kozyrev that we would put the question again, there is no need to use a veto

He says not now. We've demonstrated, and it's all good.

These are the tricks. They were.

[15:02] [I] You raised the issue of the Security Council.

Maybe two words could say about the role of the Security Council and its possible reform?

[15:13] [V] I've been watching the Security Council for years.

I've been with the United Nations since '54 attending meetings at the General Assembly of the Security Council.

I'll tell you, it's only with the end of the Cold War the Security Council is finally working as it is supposed to by statute.

It became involved in all those matters that are mandated by statute.

It began to address the issues.

And the solutions were the most interesting and the most unexpected in terms of past practice.

One such first was this decision on Iraq's aggression into Kuwait.

It was a unanimous condemnation of this aggression.

It was a call to all countries to stop all relations with the aggressor, calling on all countries to stop trading, this and that.

It was kind of like an order.

That the Security Council has the right to do, to order, and we got from 180 countries that were then members of the UN.

The answers, and the answers boiled down

to the fact that we were received your instructions, we carry out so-and-so, so-and-so, so-and-so and so-and-so.

[16:26] Here's the Security Council at work because it has to work in a normal international co-operation environment.

This was unusual in the highest degree.

I'll always remember that. How?

The way it should be, the way the founding fathers of the United Nations intended it to be.

Co-operation and universal implementation of the decisions that are made.

Therefore, the role of the Security Council immediately increased.

It jumped up in the Security Council itself.

It affected us quite severely, because we had to really painstakingly work to agree on solutions.

[17:06] Before, it was just nothing fits here.

Veto veto and that's it.

Everything is dumped in a basket.

It's pointless to veto it now, we have to come to an agreement.

But in order to negotiate, you had to sit for days and nights.

We literally spent nights drafting one resolution or another, We spent a lot of time, but we got a good solution, agreed upon, implemented.

And now this tradition is continuing already.

We, the Security Council, work by statute, and everything it does is done very right.

[17:42] It's not right when the Security Council has been bypassed by one country or another in certain cases.

[17:48] How the United States bypassed the Council Security in its military action against Yugoslavia?15

It was wrong, and it should not be repeated.

This is something to be avoided in the future.

All issues can be dealt with through the Security Council.

There is no cold war, no confrontation, no ideological struggle.

There is a shared concern for the world, about restoring peace, avoiding aggression, avoiding war.

This is all a task for the Security Council, and it is one that the Council is well placed to handle.

[18:18] [I] About reforming how it could be reformed, let's say?

[V] Well, I'll tell you.

I've been associated with this reform for a long time and when I was a representative here at the UN.

We discussed, we worked.

You see, the Security Council, a lot of people insist should be, increase the quantitative composition.

Everyone wants to get on the Security Council.

Well, not only prestigious, but really

this and it is important in terms of participation in the development of solutions of global significance.

But 190 countries can't get on the Security Council.

That makes absolutely no sense.

[18:54] But making it even very big is not the point either.

There are 15 members, it's hard to negotiate.

You can expand there to 22 more members but it'll be even harder to negotiate.

After all, all countries, all have their own way of looking at things.

There is no cold war, there are their own interests, their own view of the world.

And if you inflate it to 40 countries, for example, it will choke.

The Security Council will stop, it won't.

Will be able to work, he won't.

Will be able to work, as it will have to.

Each country will put forward its own suggestions, considerations, amendments, additions.

The whole case will stand.

It will not be able to make quick, prompt and efficient decisions.

Therefore, this should not be forgotten.

On the one hand, the desire The need for countries to join

the Security Council is understandable, while on the other hand, the need to maintain a small body governing - 20, 22, at most 25.

[19:48] I don't see the opportunity for any more because it would no longer be a working body, it would be a discussion club.16

[19:54] [I] Yuri Mikhailovich, perhaps you would like to conclude something I didn't ask?

Do you have a lot?

[V] They asked, and my experience here at the UN has still left a lot to be desired

No, I just wanted to say that The United Nations is very important.

There are occasional attacks on it from one side or the other.

that it's inefficient, inefficient, inefficient, inefficient.

But it's very important, because somehow we've been joking here with the delegates,

[20:23] let's have a competition to create a new organisations, we're about to put all the proposals together and you know what we'll get?

It'll be the United Nations all over again.

It's the same thing, but it's better to come up with a better idea. You can't.

When you're talking about an organisation with 190 countries around the world.

That's why it needs to be kept,

to take care of, to move all the issues that need to be dealt with,

not somewhere in some military alliances, but in the United Nations.

Co-operation is now assured here.

No one will veto anything now, that's quite obvious.17

And I tell a lot of people that we need to get the right written into the statute right now correctly

[21:01] A veto is not a right to stop a decision, it is a duty to harmonise decisions. That's what a veto is all about.

A veto is not a right to stop a decision, it is a duty to harmonise decisions.

So we are duty-bound to sit around and work and to agree on a solution, not what to say, and by vetoing it, walking away.

The Organisation [the UN] is important, very important. And it'll survive, nothing will happen to it.

[21:25] Many, many dozens and dozens and dozens of countries directly involved in it existed with blocs, alliances, arrangements.

It is the one who unites all the countries of the world big and small.

And little ones especially are very important. Big ones, too.

[21:42] Thank you very much. Thank you.

The newspaper clippings

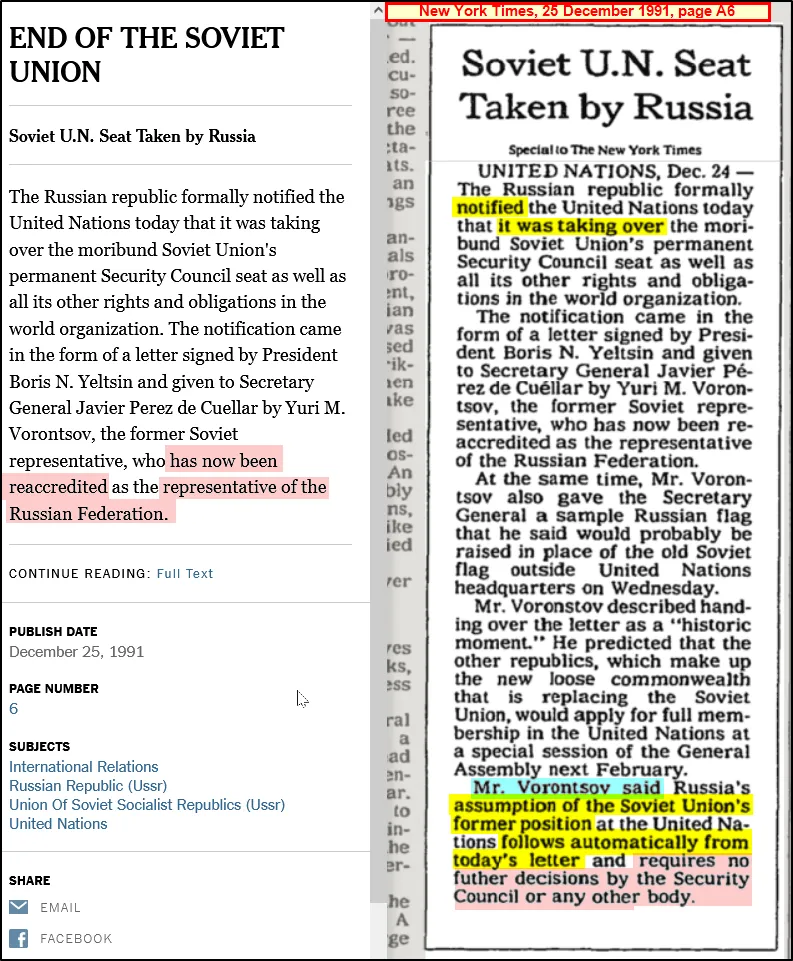

New York Times, 25 December 1991, page A6 “Soviet UN Seat Taken by Russia”

According to this report, dated 24 December 1991 (the date Vorontsov “transmitted” the Yeltsin letter), :

Vorontsov “has now” been re-accredited as the Representative of the Russian Federation”;

Vorontsov stated:

Russia’s assumption (sic) of the USSR’s “former” position at the UN “follows automatically from today’s letter”; and

it “requires no further decsions by the Security Council or any other body”.

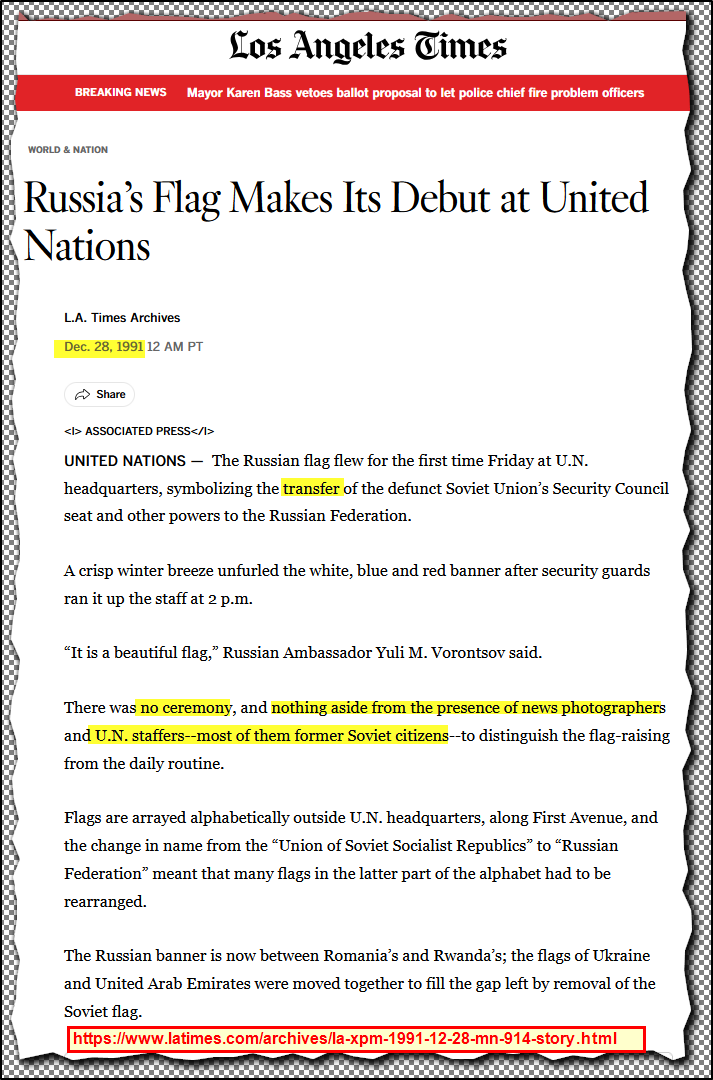

Los Angeles Times, 28 December 1991, “Russia’s Flag Makes Its Debut at United Nations”

“ ‘It’s a beautiful flag,’ Russian ambassador Yuli M. Vorontsov said.”

“There was no ceremony, and nothing aside from the presence of news photographers and U.N. staffers—most of them former Soviet citizens—to distinguish the flag-raising …”

The UN Charter expressly limits non-member coutries communication with the UN to

Article 35: “bring to the attention of the Security Council or of the General Assembly any dispute to which it is a party if it accepts in advance, for the purposes of the dispute, the obligations of pacific settlement provided in the present Charter.“

And Article 32: “if it is a party to a dispute under consideration by the Security Council, shall be invited to participate, without vote, in the discussion relating to the dispute. The Security Council shall lay down such conditions as it deems just for the participation of a state which is not a Member of the United Nations.“

See, for example, the record of submissions and exerceise of the Security Council Presidency on 15 December, and in the closed Security Council meeting about Yugoslavia on 20 December.

See the absence of support, and deafening silence on the question of the UN memberships (no doubt they quite enjoyed being alive) - in Gorbachev’s resignation speech the following day, and the Supreme Soviet’s declaration the day after that. Reproduced at:

Vorontsov video at the top of this page, at 03:40.

Nigeria held the General Assembly presidency from September 1991 to September 1992. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to speculate what Nigeria’s response would be if told by Russia to depart from the normal practice of circulating such letters to all Members and placing it on the General Assembly agenda. Co-incidentally the annual report of the Security Council to the General Assembly for June 1991-June 1992 wasn’t released until June 1993. The Secretary-General, Perez de Cuellar’s appointment ended on 31 December 1991. His file on USSR from September 1991 to 27 January 1992 has never been released.

The exact words used in the Yugoslavia case publicly being considered at the exact time this was being done. See footnote 5.

There is no record in the UN public records of any such phone opinion. If advice was given, it is nothing more than an opinion. Any such opinion is not binding.]

"whatever you decide at the UN” of course is correct. However UN Charter sets out the requirements for decisions of the UN, and they have never been complied with, so there has never been a valid decision. It does not mean inaction, or a sleight of hand by a few individual actors.

THIS is the real legal ruling on the point - inexplicably omitted by Vorontsov in his recounting of the “international Court of Justice” phone call; and by commentators for 33 years: the general rule applies, unless the UN makes a valid decision otherwise, which has never occurred.

A dissemblance that would make Trump’s legal team proud. In fact the law on “what Russia had” was very clearly set out in 1947.

That very law was being correctly and openly applied in the case of Serbia and Montenegro (renamed “Federal Republic of Yugoslavia”)’s claim to “continue” the membership of the Federal Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia, at the exact same time the Russian impostorship was being hidden. See the comparison at: Comparison - circulation of documents in the near - identical claim by Serbia and Montenegro to “continue” the UN membership of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

All 15 members of the USSR joined the USSR as existing states, and continued to exist throughout as equal members - see the documents under the heading “Was Russia ever the USSR?“ in Images - Russia and the UN. States emerging from division of states were called “new” in the 1947 declaration of the law, that such “new” states could not claim membership of the UN, until they had been formally admitted under Article 4 of the Charter.

Nobody was notified or given any opportunity to even consider, let alone question it, let alone vote as required by Articles 4 and 108 of the UN Charter. It seems Vorontsov, as President of the Security Council at the time, simply persuaded the Secretary-General to implement it, without any legal authority to do so. The Secretary-General apparently accepted the credentials of Vorontsov as UN Representative of a state that was not a member of the UN, and changed the name of a member that had not requested it to the name of another state, on the spot, 24 December 1991, and no further action or decision was taken. It was presented as a name change.

18 months later, in June 1993, the first reference to the contents of Yeltsin’s letter was buried in an unlabelled “note” in a late-published annual report from the Security Council to the General Assembly, under the heading “received but not considered by the Security Council”. Categorical proof that it never went even before the Security Council let alone the members. In another document, the OCR text contains a space between each character of “Russian Federation”. So it is not searchable in the document or in the UN records. See further:

members could do nothing about a name change, that is an internal decision of a country, updated in the UN by an administrative procedure. There was never any meeting about the USSR’s UN memberships. It was never placed on any agenda. There was no report about it. The letter was “not issued as a UN document” so there is actually no public UN record that any members (even the 3 mentioned by Vorontsov) ever saw it or knew of it.

The first recorded mention of a letter, or “continuation” in public UN records was 18 months later, buried in un-indexed notes at page 313 of 355 of an “advance version” of the mandatory Security Council Annual Report released on 2 June 1993, at the end of a section headed “MATTERS BROUGHT TO THE ATTENTION OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL BUT NOT DISCUSSED IN THE COUNCIL DURING THE PERIOD“. The final report was not released until 1997. It contained the same un-indexed notes with 2 minor cosmetic changes, at page 277 (actual document page 294 of 333). Ibid.

The flag was changed on 28 December 1991, while the General Assembly was not in session and most personnel were likely to be on holiday. There was no ceremony, no UN record (cf the notifications of other countries’ name changes to the General Assembly members), no one was present except a few, mostly ex Soviet staff, and photographers - https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-12-28-mn-914-story.html

This is a strange comment, the reality being that Russia was the fist to secede (after the Baltic states left), an presumably actively encouraged the remaining republics to do so. The legal reality was that while they remained in the USSR, they had what remained of its structures and power, and the UN memberships and veto.

NATO bombing of Yugoslavia - Wikipedia

1999 - NATO countries attempted to gain authorisation from the UN Security Council for military action, but were opposed by China and Russia, who indicated that they would veto such a measure. As a result, NATO launched its campaign without the UN's approval, stating that it was a humanitarian intervention. Supporters of the bombing argued that the bombing brought to an end the ethnic cleansing of Kosovo's Albanian population, and that it hastened the downfall of Slobodan Milošević's government, which they saw as having been responsible for the international isolation of Yugoslavia, war crimes, and human rights violations. Critics of the bombing have argued that the campaign violated international law.

This is one point I agree with - KIP. Adding vetos will end the viability of the Security Council. Note: Vorontsov does not mention the wider call for limitation or abolition of the veto power itself.

[KIP - that aged like a fine milk]

What a find this audio recording was!

Apart from the inexplicable claim of a phone opinion from the International Court of Justice, Vorontsov's statements here and to the newspapers at the time (as shown in the clips in the article) give the complete picture of what happened.